Published on November 8, 2025 5:12 PM GMT

Cross-posted from https://bengoldhaber.substack.com/

It’s widely known that Corporations are People. This is universally agreed to be a good thing; I list Target as my emergency contact and I hope it will one day be the best man at my wedding.

But there are other, less well known non-human entities that have also been accorded the rank of person.

Ships: Ships have long posed a tricky problem for states and courts. Similar to nomads, vagabonds, and college students on extended study abroad, they roam far and occasionally get into trouble.

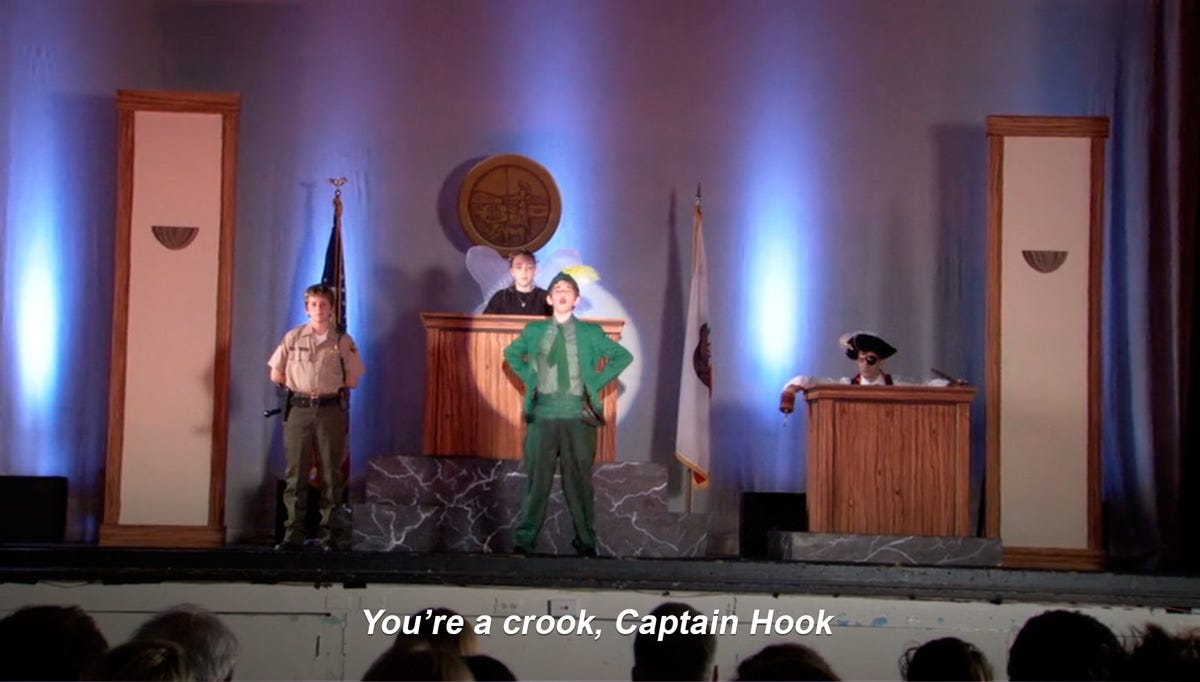

classic junior year misadventure

If, for instance, a ship attempting to dock at a foreign port crashes on its way into the harbor, who pays? The owner might be a thousand miles away. The practical solution that medieval courts arrived at, and later the British and American admiralty, was the ship itself does.

Ships are accorded limited legal person rights, primarily so that they can be impounded and their property seized if they do something wrong. In the eyes of the Law they are people so that they can later be defendants; their rights are constrained to those associated with due process, like the right to post a bond and the right to trial.

While researching this, I did encounter a cool, almost-a-right that ships have - the right of salvage. If Ship A encounters Ship B in distress, and comes to save it, then Ship A can get a reward, if and only if it it’s successful (under the delightfully named “no cure, no pay” principle). A binding contract is created once Ship B accepts the offer of salvage; the reward is determined later by arbitration - if the two crews agree to the widely accepted standard practice of using Lloyd’s Open Form, a general convention established by the insurer Lloyd’s of London - or by a maritime court.

And salvage law is one of the oldest laws on the books. Rhodian sea law, from 900 BCE, states that if a salvor rescues property from the perilous seas, they are entitled to a share of the saved property. The Romans later adapted this to a general monetary reward.

I say this is almost a right, because as far as I can tell salvage rights are used by the captains of the vessels, acting as representatives of the owners, and are not assigned to the ships themselves.

This discursion made me wish I was a maritime lawyer.

Maritime law. Lawyers of the sea.

The Whanganui River: In 2017 the New Zealand Parliament passed the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act, which granted the Whanganui river a ‘legal personality’ and endowed it with “all the corresponding rights, duties, and liabilities of a legal person”.

The act resolved a lawsuit and dispute extending back to the 1930s. The Maori Tribe claimed that the steamboat industry and mineral extraction promoted by the colonial government were degrading the river, which they view as an ancestor and source of spiritual value. They petitioned the New Zealand government to accord it legal status.

When the New Zealand Parliament passed the act, it granted $80 million dollars for restoration of the river, $30 million dollars for a forward looking fund to advance the river’s best interests, and, along with the legal personhood, two custodians - one from the government and one from the Maori Tribe - to represent the River.

Reading about the Whanganui river I expected a relatively cut and dry legal case; something more like giving a Superfund site a representative to address politically and religiously sensitive claims.

Reading the act itself you get a much different impression:

Te Awa Tupua is an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements.

Te Awa Tupua is a legal person and has all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person.

Te Awa Tupua is a spiritual and physical entity that supports and sustains both the life and natural resources within the Whanganui River and the health and well-being of the iwi, hapū, and other communities of the River.

It’s more like the New Zealand parliament reified a god and gave it a multi-million dollar trust fund to get on its feet.

I find it a very endearing aspect of the administrative state that it recognizes that even the indivisible and living spiritual base of a region will have to answer to the taxman, and so the act states it should “apply for registration as a charitable entity under the Charities Act 2005”.

Lord Rama: There are more deities that exist in both the heavenly and legal planes. In Indian law Hindu gods and their idols are considered “juristic persons”, granting them standing to own land and defend their interests in court.

Hindu deities are legal persons who represent the idealized purpose of pious worship by their devotees. They own property, but only in a legal sense. They require fiduciary guardians to act on their behalf and, when their guardians break their relationship of trust with the deity, other worshippers can file suit on the deity’s behalf.

The legal status of Hindu deities stems from British colonial rule. The temples held vast amounts of land and wealth, and the British administrators, like the maritime courts, had to answer practical questions like “who owns the property”. It couldn’t be the worshippers as a whole - an undefined, constantly changing group - and it couldn’t be the “shebait” (temple manager) who might misuse the money or pass it to their heirs. Rather, Rather, the Bombay High Court in 1887 recognized the deity itself as a juridical person, and that there were “next friends” who represent the god.

It’s not clear to me how a specific next friend is established - what if the god has a lot of friends? The 1887 ruling makes it seems like quite a bit of what the Judge was adjudicating was whether the administration of the temple was best serving the interests of Shri Ranchod Raiji, and thus who was more of a ‘fake friend’.

More recently there was a high profile case involving disputed land in Ayohdya, which Hindus consider to be the birthplace of Rama, a major deity in Hinduism (you may have heard of the Ramayana). There was a long running dispute on whether a mosque that had been erected on the site was infringing, in some sense, on Rama’s property. In 2019 the Indian Supreme Court awarded the land to Rama Virajman, and a trust was established to manage the property.

There’s an interesting through line with Whanganui River personhood: the legal rights of the divine most often come up when land is contested between different faiths and sects (Hindus and Muslims, the Maori and Industry).

And, like the river and ships, the bundle of rights given to the Hindu deities are not a one to one match with the ones people possess:

In the case of Sabarimala (Indian Young Lawyers Association & Ors. vs The State of Kerala & Ors, one of the arguments put forward against allowing women of menstruating age to enter the temple was that this would violate Lord Ayyappa’s right to privacy, who is eternally celibate.

The justices did not accept this argument, noting that having some statute rights “does not mean that the deity automatically has constitutional rights”.

Thanks to Gabe Weil, and the authors of A Pragmatic View of AI Personhood, for bringing this whole area to my attention. Remember that I am not a Lawyer, and none of this should be considered advice on whether it’s a good idea to give rights to non-human entities.

Discuss