Ours is a remarkable moment in world history. A transformative technology is ascending, and its supporters claim it will forever change the world. To build it requires companies to invest a sum of money unlike anything in living memory. News reports are filled with widespread fears that America’s biggest corporations are propping up a bubble that will soon pop. Behind the scenes, a political backlash is fomenting, as the forces of anti-oligarchy and anti-monopoly are rising.

Is this the artificial intelligence boom of the 2020s? Or the transcontinental railroad construction of the late 1800s?

Between the 1860s and the 1900, the transcontinentals transformed America. They populated the west, birthed the modern corporation, turned the U.S. into a coast-to-coast dual-ocean superpower, and revolutionized modern finance. As the historian Richard White wrote in his epic history of the transcontinentals, Railroaded, “they created modernity as much by their failure as their success,” leaving behind “a legacy of bankruptcies, two depressions, environmental harm, financial crises, and social upheaval.”

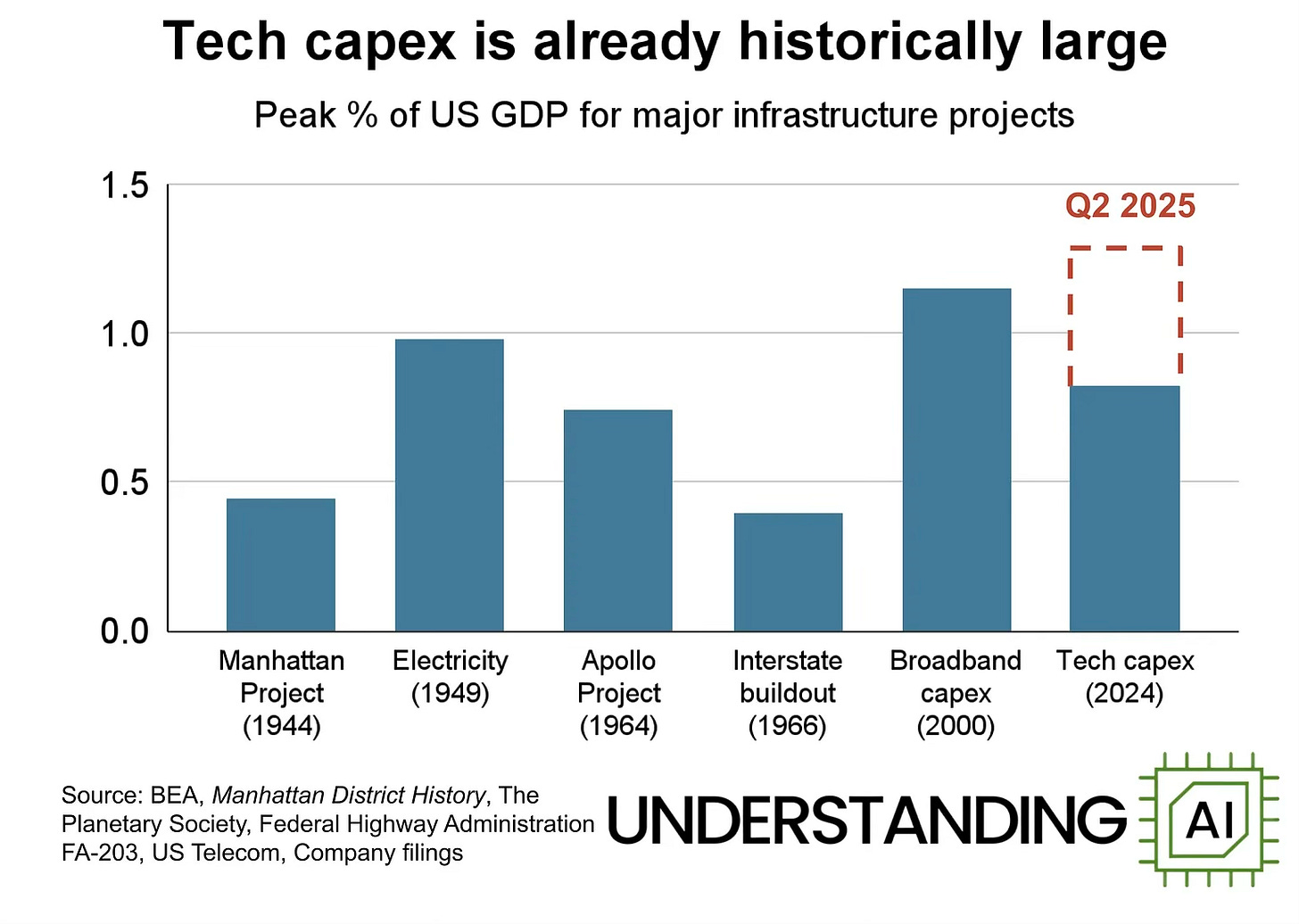

In the 2020s, AI is already transforming America in a similar fashion, driving overall economic growth and powering the stock market to all-time highs. As a share of US GDP, the AI build-out is on track to exceed every major technology since—you guessed it—the railroads.

If artificial intelligence changes the 21st century as much as the railroads changed the 19th century, we should brace ourselves for something deeply strange:

The railroads changed forever the way we think and work. In Time Travel: A History, the author James Gleick suggested that the railroads so warped our sense of time and space that humankind invented the concept of time travel as a reaction to the compression of distance and the invention of time zones.

The railroads also changed the way we organized and managed work, giving rise to the occupation of “manager.” In The Visible Hand, the historian Alfred Chandler argued that the railroad (along with the telegraph) made necessary large, professionally managed corporations, thus creating modern managerial capitalism.

The railroads changed politics, by creating the modern lobbying industry and transforming the government’s relationship to the private sector. In his 19th century histories Railroaded and The Republic For Which It Stands, the historian Richard White argues that the railroads were the industrial chrysalis from which sprung from entire Gilded Age and the second industrial revolution.

Today, I’m running an edited and polished transcript of a recent conversation I had with the historian Richard White about the age of the railroads and what their history might tell us about the age of artificial intelligence. As you’ll see, the number of parallels are uncanny. Our conversation touches on:

Why the original goals of the transcontinental railroad had little to do with the final construction

How the politics of anti-monopoly evolved into the Progressive Era and the New Deal

How trains changed our sense of time, space, and work

Why the railroad bubble popped—again and again—and what its popping might tell us about AI

Throughout our conversation, I’m going to include annotations that connect the history of the railroads to the modern story of the AI build-out.

THE AGE OF THE RAILROADS

Derek Thompson: How did the transcontinental railroads get started? Why did we want to build them, in the first place?

Richard White: Initially, the reason the government financed the transcontinentals was to keep California in the Union during the Civil War. The railroads get started in 1864 when the war was still going on. But the war was long over by the time the railroads were going to be completed in the late 1860s. The transcontinentals were supposed to let the nation move goods across the continent more cheaply than it could by going across Panama. In fact, eventually the western railroads, Union Pacific and the Southern Pacific, would buy up the Pacific Steamship Company to raise rates, because they could not compete with a steamship company moving goods across the country.

The railroads were supposed to introduce an age of competition, individual fulfillment, and small farming. But in fact what they did is they created large corporations—both incredibly competitive and monopolistic—that controlled the economy.

Thompson: With the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864, Congress granted two corporations land and bonds to build a transcontinental railroad. You called these laws “the worst acts that money can buy.” Why?

White: What they do is essentially have the government take on all the risk and guarantee the profits to private corporations. They also give the money to people who know nothing about railroads. One of the first calculations made by people who actually ran railroads in the east is that there’s no way in the world these roads are going to pay for themselves. There isn’t the traffic for them. They’re going to be immensely costly. The 1864 Act had to literally double the subsidies to get them to go.

The men who get immensely rich from this knew nothing about running railroads. What they know about is getting subsidies. What they know about is getting loans. And what they know about is draining these corporations of profits while leaving the cost to the stockholders and bondholders. They can do that because these railroads are incredibly corrupt. I mean, they don’t invent American corruption. It’s much older than that, but they bring it into its modern form. They’re the ones who create modern political lobbying. They’re the ones who buy Congress by and large. They’re the ones who throughout this period will always be giving favors to what they call their “friends” who are politicians, bankers, businessmen, who, by and large, will do them favors in return. What they do is create an incredibly unstable economy.

With the great crashes of 1873, and again in the early 1880s, and the 1890s, what you have is a boom-bust economy. Most of the busts begin with a railroad depression. The transcontinentals were central to those railroad depressions.

INTERLUDE #1: Even in these early answers, you can see both a difference and similarity between the transcontinentals and AI.

A difference: The transcontinental project was government-financed from the jump. It was launched as a wartime strategy to keep California in the Union and backed with government loans and land grants. The AI buildout, by contrast, is overwhelmingly financed by the richest companies in the private sector.

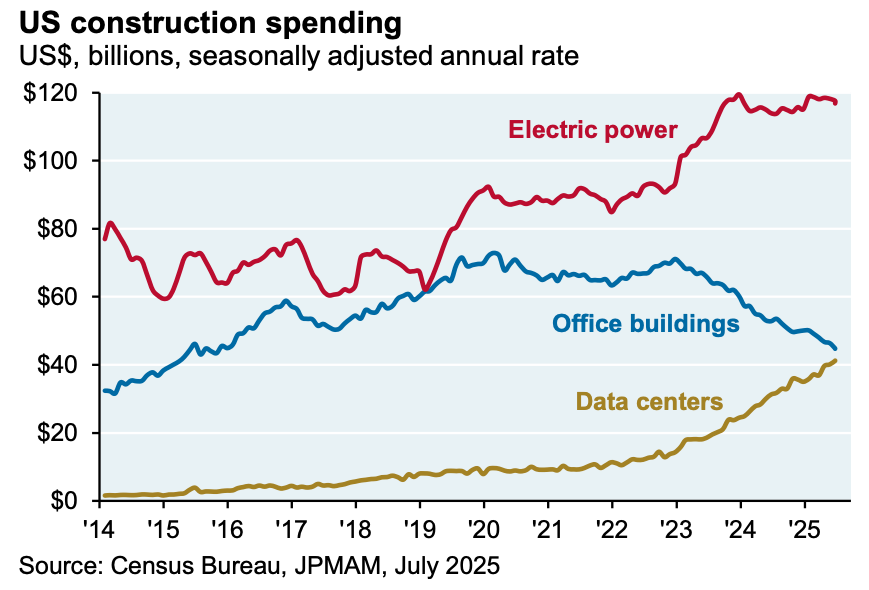

A similarity: The transcontinentals were “central” to the U.S. economy in the second half of the 19th century—so central, in fact, that whenever the railroads caught a cold, the entire economy sneezed. In 2025, AI is similarly eating the entire economy—from the stock market (AI-related stocks have accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns since ChatGPT launched in November 2022) to the construction industry. According to JPMorgan, data centers “are eclipsing office construction spending” and pushing up electricity prices across the country.

HOW AMERICA FINANCED THE TRANSCONTINENTALS

Thompson: Building the railroads required an ungodly amount of money, many years before the financial instruments we rely on today. How did they pay for all that?

White: The railroads were built on other people’s money. The first general rule is that the people who ran these railroads never, if they could possibly prevent it, used their own money. So the federal government had to offer a series of guarantees. The guarantees—to simplify a little bit—were: We will guarantee the bonds that you issue, they’re going to be the responsibility of the federal government, so that the bondholders are not going to lose if you go under. We will redeem those. Secondly, the government made it possible to redeem bonds by handing out tremendous land grants, which companies could sell to settlers. By paying for the land, the settlers would help the companies repay the loans to the government.

What the railroads found was that even with the government loans, they could not afford to build. What they had to do is be able to get other capital. Capital in the United States was scarce. The United States was land-rich, but we’d come out of the Civil War as a heavily indebted nation. The kind of capital that’s going to be necessary to build these roads is simply unavailable to them even in New York.

Thompson: If the railroad companies couldn’t get all their financing from the U.S., where did they go?

White: They have to go to Europe. They’re going to have to bring in heavy European finance. Particularly, they’re going to get a lot of it from Germany. They look to England. The Rothschilds look at this stuff and won’t touch it.

What they do is they start a series of bond issues, which bypassed Jay Cooke, who had been the leading financier who helped the Union during the Civil War. They issue bonds on everything. They’ll issue bonds on their equipment. They’ll issue bonds on their track. They’ll issue bonds on the land grant from the federal government, even though this was violating what they’re supposed to do. They’re not selling the land as the law demands. They’re actually using it as collateral now for loans. They will issue bonds on that. Eventually, they’ll issue bonds for future profits.

They’ll issue bonds on anything you can possibly imagine, and then they will try to float these bonds through New York bankers who will operate in Europe. Since nobody will touch them, these bonds are heavily discounted. To get $100, they issue $100 bond, but they might get 75 or $80 on the bond. Already the debt is beginning to pile up all around. They become heavily, heavily indebted corporations existing on borrowed money.

The promise of the profits was always going to come from selling these lands. But selling the lands became very, very hard in places like Utah, Nevada, the Western Great Plains, where in fact once you got people out there, there was nothing for them to produce. The railroads opened up minerals and, further to the east, crops. But these crops glutted the market. The economy was beginning to suffer from too much of virtually everything. They get abundance. But it’s like Disney’s “the Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” Once Mickey Mouse starts this thing going, he can’t turn it off.

What you’ve created is a mountain of debt, a monument to debt. The genius of these guys is that they realize that debt can give you immense profits as long as you are not the one responsible for the debt. There’s all kinds of corruption that goes on with this.

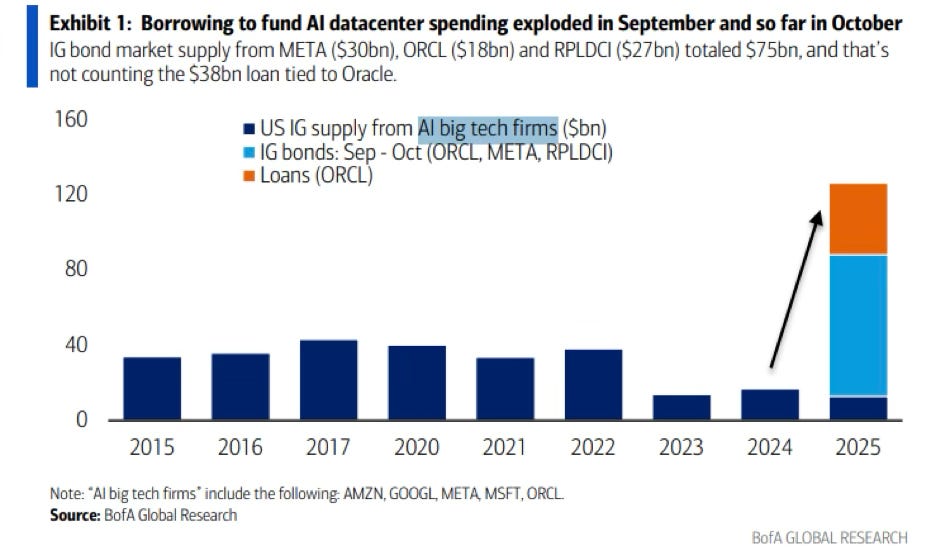

INTERLUDE #2: The railroads were built with debt. Debt, debt, debt. The whole thing was a tottering Jenga tower of leverage, and it came crashing down every 15 years or so. By contrast, the AI buildout has not relied significantly on borrowing. Most data center construction to date has been financed by free cash flow from the major US tech companies with capital from private-capital firms like Apollo and Blackstone.

But this might be changing—and fast. Last week, Bank of America Global Research reported that “borrowing to fund AI datacenter spending exploded in September and so far in October,” illustrating said explosion with the graph below. “The implications [of this] are profound,” wrote Doug O’Laughlin in his Fabricated Knowledge newsletter. “What had been a disciplined, cashflow-funded race may now turn into a debt-fueled arms race.” I’ve spoken to a lot of smart analysts, such as Doug, who say this debt bomb is the sort of thing that should make folks worry that AI could be a big bubble.