Published on October 8, 2025 1:48 PM GMT

O

And One

And Two

And Manifold

Are the 万

Among the skies

If our understanding of physics is to be believed, the world as it really is, is an unfathomably complex place. An average room contains roughly 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 elementary particles. An average galaxy is made of roughly 100,000,000,000 stars (enough space and material for maybe 1000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 rooms in each of those star systems for humans to sit in and ponder these numbers). An average human has roughly 1000,000,000,000 sensory cells sending sensory signals from the body to the brain. The human brain itself has 10,000,000,000 neurons to create an unbelievable amount of different impressions on human consciousness.

Because of combinatorial explosion, the possible number of exact inputs a human mind could receive is even more mind-bogglingly big than all of these numbers. It is so big in fact, that any of the numbers I have mentioned could be off by a factor of a million and the general impression of the endlessness of being in the human mind would be practically unchanged.

Even though the human brain is quite large the human mind is seemingly incapable of fully encapsulating the even larger universe fully in itself. It seems impossible to compress the state of the world losslessly. Since we live in this world however, and since we have to function to live, all things that live and act in the world had to find ways to handle this irreducibility of complexity. The way to handle it, most generally put, is to use lossy compression of input into simplified models that only keep the information that is relevant for survival and flourishing. Animals do this by turning the formless sensory input into distinct objects that can be put into different categories and used to build simplified object relations maps. These models can be used to extrapolate from current observations to likely future sensory inputs and how they will be influenced by personal behavior.

It is important to note here that the extrapolations concern themselves with what is important for the animal. The information compression is not value neutral. These models will not be useful to determine how the animals behavior influences the positions of elementary particles or dust specks. What they are useful for is to determine useful things for the animal. How to get food, how to mate, how to avoid danger. This way a soup of nerve signals becomes a ground to walk on, a sky to fly in, a jungle to hide in, food to eat, a partner to mate with, a predator to hide away from or prey to hunt.

The more complex the animal's nervous system is, the more complex the models can become. Social animals are able to differentiate between kin and general allies, neutral pack members and rivals to fight. Tool-using animals are able to use a stick as a hammer or as an elongated appendage, depending on their concrete needs at that moment. Even more intelligent animals are able to simulate the interactions of varied social relationships in their groups or are able to think about objects as tools in complex reasoning chains of problem solving plans.

Manifold the many paths of Labyrinth

Manifold the steps

Manifold, Manifold, Manifold

the thoughts

the words

the deeds

To walk upon them wisely

To not get helplessly confused

That is the Quest of Manifold

That each traveler must chose

Humans - like other animals - are able to use their modeling abilities intuitively. There is no need to understand how you are doing it, when you are able to correctly understand that there are two cups standing on your kitchen table, but you need one more because you have two guests in your apartment who want to drink coffee with you. From all the sensory input you get your brain is automatically able to form basic concepts like tables, cups and coffee and more complex concepts like numbers, the desire of other people for coffee or the concept of drinking coffee together as a social activity. You needed some time to update into the exact shape of your current models from the evolutionarily pre-trained priors you had at birth. Now that your models have been shaped to model your environment well there is no more effort you have to take to make use of them.

One problem with this approach of trying to tame Manifold however is that when trying to model more complex, more subtle facts about reality humans constantly run up against the natural limits of model size they can hold in their heads. Already in day to day social interactions humans have to use fundamentally inaccurate simplifications in their modelling to be able to function effectively. When we notice that the cashier at the grocery store checkout was mean to us we model them as an asshole instead of trying to simulate all their complex context dependent motivations to behave this way. To work through the complexities of life we constantly simplify the world and use compressing narratives to be able to hold a sufficiently useful image of reality in our head.

Frames of frames of fickle frames…

Of maps of maps of meanings maps…

Lead you through the Manifold

To א or to ε

Or to the Void from which they came

And the path that shall be taken

Is set by what it means

meanings golden star though

Varies beast by beast

Your א stars to me are empty

Too meager for making maps for two

While the northern lights in myself

Are just blinding noise to you

What a path means to a traveler

Depends from whence they came

Every path in endless desert

Makes a million million different ways

»But is there not One Way to wander?«

Wonder wanderers at night

No one knows

But we’ll keep trying

To see in colors

To which we’re blind!

The way I have talked about this topic so far is one of the ways that Manifold can be approached. It is far from the only possible way. There are many possible paths, many possible frames that can be valuable. Which one is good and useful depends on what you are looking for. It happens so that as I was discussing the mysteries of Manifold with my friend υ. She felt an urge to share her own perspective on its lands and the frames one can hold within it. I much liked the path υ took me on so let us make a detour into a different (though related) frame:

To me, making sense of the world is fundamentally about imbuing it with meaning. Simplifying and compressing its complexities happens in service to that. What is going on around me? What is my place in this? What is within my reach? What can I do with it? How can it affect me? My mind is constantly trying to answer those questions, which is why I can move through a world that feels coherent. And while I take my answers for granted in day-to-day life (of course, the world is full of friends, strangers, memories, objects, places, wars, loves, treasures, worries, time!), those building blocks are not universal. What is a friend to an alligator? Someone you live with side by side until you eat them because they had a seizure? What does sunlight mean to you when your body does not produce heat? What is air when you can hold your breath for hours?

Other animals are not the only ones who interface with the world in alien ways. We all start at a rather weird place – as infants. I perceive a thing. What can I do with it? I can throw it, and when it hits something solid, it makes a delightful sound! Except if it’s a human, then it makes an angry sound. Aha, it is made of two parts! If I take away the smaller part, I can clip it onto something. And with one side of the bigger part, I can make traces! If I break the big part, black liquid oozes out of it. A disapproving sound. As adults, we know that a pen is simply a tool to write with.

Some people accept that alienness gracefully. Alligator handlers understand that working with wild animals could lead to grave injury or even death. My mom was incredibly patient with my baby sister. Do we have the same grace when it comes to people “like us”? Go back a few sentences. Did you notice how I claimed that adults see pens simply as tools? Surely, there must be plenty of adults for whom a pen is more (or less) than that. What we accept for noticeably alien minds is often harder to tolerate in those we deem similar. That first and foremost goes for myself.

In the past, I tried hard to make people buy into my interpretations. Because of that, I would get into drawn-out fights, putting friction on my relationships. It was inconceivable to me that a "similar-minded” person wouldn’t come to a similar conclusion. If we just talked for long enough, if I just found a way to explain myself – and there surely was such a way – then they would accept my view. Right? That’s how I lost some friendships. Since then, my perspective has started to shift. Just because we look at the same world and use the same words does not mean that our minds make meaning the same way. This is a simple insight, yet it is sinking in slowly. Let me take you back to an encounter from a few months ago to show you what I mean.

Late one night, I was chatting with friends. One of them shared an anecdote about a phone call he received from a new acquaintance.

“Why are you calling me?” my friend asked.

“Oh, because I wanted to chat with you!” came the reply.

“It’s fine if you lost a bet and had to call. You can just tell me.”

“No, I called because I wanted to chat.”

“I won’t be angry with you. Just tell me the truth, that’s all I care about.”

“I simply wanted to talk.”

“Why won’t you tell me the real reason? Again, it doesn’t matter what it is as long as you tell me!”

Their conversation continued like this for a bit. The new acquaintance didn’t call again.

Now I was convinced that I knew what the story was about. My friend was bad at socialising and too distrustful, which made him jump to conclusions. I was tempted to discuss the matter, trying to win him over to my side. But then again… What did that call mean to him? Had he been in a similar situation before, finding out that someone approached him with an ulterior motive? Was he rejected over and over in the past, making it hard to believe that strangers would want to become friends? Maybe a phone call is a formal affair to him, or reserved for emergencies, and friends just text each other?

I don’t know what went into his interpretation, and on some level, it doesn’t matter. What I want to internalise is that my way of making sense is not inherently superior. However, even while I’m typing this out, I cringe – because when I try to imagine my friend’s interpretations, everything I come up with feels absurd. Only my own interpretations feel reasonable. Talking about the vast space of meaning-making is more of an intellectual acknowledgement than a deeply felt intuition. And while I mostly stopped losing friends over diverging interpretations of world states, I am still deeply immersed in my own stories, my own values and my own expectations. Bridging a gap of meaning is hard. My narratives absorb me, and my imagination is not strong enough to pull me out. I live in my narratives. “This is what it means”, my mind tells me, and I’m nodding along fervently. Can I be a slightly different person?

What kind of person would I want to be? Could I let go of the expectation that I can make people understand? Could I look for ways in which a foreign frame resonates with me, even slightly? Could I take my structures of meaning seriously without living in them constantly? Could I accept that my frame is one of many possible ones? Could I shift from “This is what it means” to “This is what it means to me right now”? Could I reach for a good faith interpretation instead of dismissing a foreign narrative? I have immersed myself in novels, movies, games before told in voices very different from mine, letting them be my guide. Could I apply this flexibility to engage with other minds? And, maybe the best next step for me, could I build tolerance for being misunderstood and just let people call my frames absurd?

These are some questions on my mind right now. At the same time, more might be possible, even for me. I think that sometimes, for a fleeting moment, I could do more than being patient and acknowledging other minds in all their strangeness. Maybe I could disrupt my own immersion – put some distance between me and my narratives. From that viewpoint, I might catch a glimpse of a world that’s strange – big, expansive, shimmering in colours seldom seen before.

The King of kings of narratives

Sits upon His throne

The bards and jokers of His court

Play for Him Alone

The Hymn of hymns of Labyrinth

Rings among His own

The princes and the servants too

They mock and sneer and scorn

But the Land of lands of Manifold

Is not kind to those that sneer

The deserts of King Manifold

Grind to dust which disappears

It felt good, felt helpful to see in a different color and to walk a different path with my friend for a while. But now I want to return to the path I had set out when I started writing. I want to expand more on what frames can evolve to when we share them with each other and try to build them into bigger and bigger structures.

When we start to consider sociological questions the frames we construct to find meaning and sense can be amplified into frameworks through which we see the world. When we think about why there are more men in management positions than women for example, we may believe that that's because of innate genetic differences between males and females or that it is caused by societal structural forces that limit the career success of women. We may even consider that multiple factors play a role. Nearly always however our models fail to consider all relevant factors that explain these societal observations. Importantly, we also don’t choose these explanatory models independently for each question, but choose fundamental axioms that guide the ways in which we see the many different phenomena in the world. Even more than that, the frames in which we move shape the very questions we even think of asking. The frameworks we do use ultimately try to limit the complexities and nuances of thinking about very complex systems like societies into limits which can be contained by human thinking while still being useful to us. Additionally we use them as social coordination tools. As schelling points for political coordination and as stabilizers to make it possible to live in groups that share common frames.

As these frameworks are shaped socially and often politically in these ways, they don’t necessarily converge to be the same for all groups. For purposes of group cohesion they may converge in separate groups (independent of their truth merit), but for many other reasons they often fail to converge for humanity as a whole. More grounded beliefs about the cups on your table and the mood of the friend nagging you for his coffee tend to converge back, because a mistaken model here tends to have immediate consequences. (A friend leaving your flat angrily because he didn’t get his coffee for example). Modelling mistakes with less immediate feedback loops can function well for long periods of time in social reality even when they fail to accurately predict details about the complex phenomena they want to model. In this environment memetic fitness in a social environment is the dominant concern for the survival and thriving of ideologies.

As these simplified socially sustained models grow more and more involved in different sociological questions they can become ideologies. Ideologies in that sense are memetically optimized mental constructs that are able to give answers to many different social, political and sometimes even metaphysical questions by applying general patterns to the answer generation process. In the same way the ultimate answer to a leftist tends to be Class Struggle, it will tend to be Freedom to a libertarian and tend to be God to a religious conservative monotheist. While they are all inaccurate in various ways for different questions, they are able to sustain themselves through the need for model simplicity and then get selected for through memetic fitness.

That these ideologies are built up and sustained through mechanisms that are detached from finding out true facts about the world is something that has been critiqued a lot in the 20th century. The (meta?)ideology of postmodernism is one of the big groups of thought that has tried to point this out. However, many active postmodernists like Foucault or Baudrillard were active ideologues themselves (in the leftists sphere in most cases). Because of that they and many of their latter disciples often used these observations as political weapons to undermine their ideological enemies (But is that not just right-wing propaganda? Destroy the narrative! Destroy the counter-narrative! Destroy! Destroy! Destroy!)

In the level sands of Labyrinth

Kings corpses sit on thrones

And leave upon each traveler

A wish for Their own goals

In the lone lands of Manifold

Each courtly ruin is a mark

Points that lead to א’s star

On a line that marks a start

When trying to apply postmodernist thinking seriously and not as a cynical tool, it results in a radical deconstruction of narratives. This deconstruction over time removes the walls that separate the ten thousand things in your mind. However, the fundamental problem still remains. The world still needs to be explained. The mind must believe and must explain. But as new explanations are built, deconstruction continuously pulls them apart. What is left after a while is psychosis in your mind, noise among the narratives and ruins in the land of Manifold.

As you see through the untruths of narratives you will find yourself in a deconstructed world where your desire for model building will continually collide with the complex nuances of the world that your mind is too simple to model. In this deconstructed world you have to ask yourself a question. How can I start to deconstruct constructively?

א and too ε

And the Void from which they came

Encircle all of Manifold

In the 道 that bears their name

So in games of encircling

As in games of black and white

The travelers learn of the Way

of all the ways to rise

To explain yet another path among the narratives that might be useful to you it seems best to introduce you to the game (and the player) that gave me the original inspiration for this chapter.

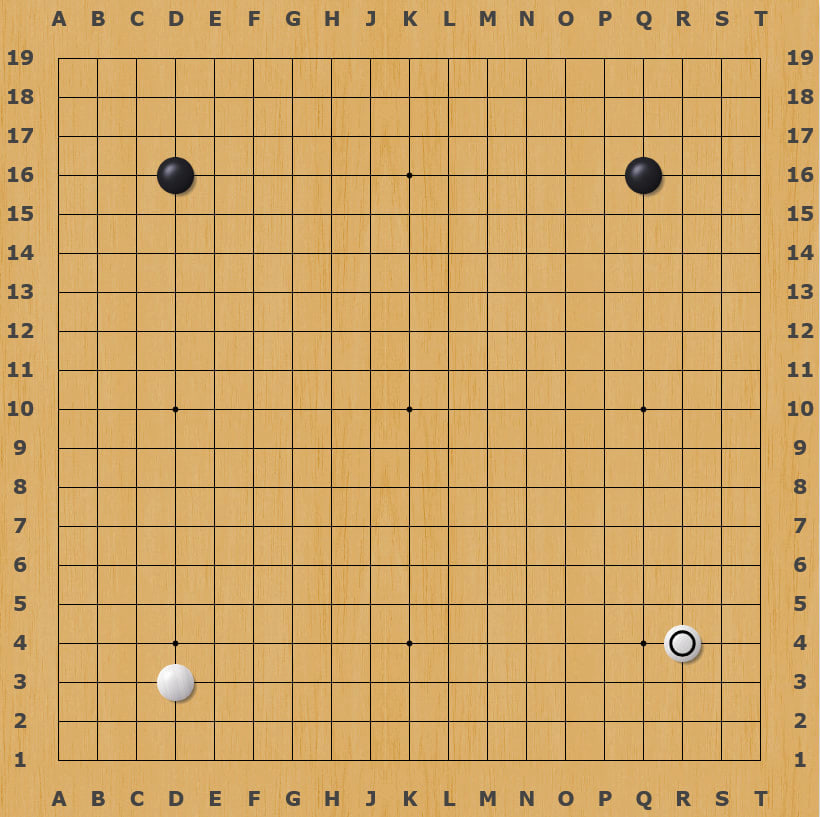

This is the game of Go. Its fundamental rules (like the rules of other Games of Manifold) can be put quite concisely.

Still out of these fundamental rules a much larger set of emergent concepts and rules for success arise. Like for the other games of life, these emergences are too numerous to list explicitly here. But for what I want to talk about it is mostly important to understand the vibe of the game anyway. One way (one framework) of describing this vibe would be this:

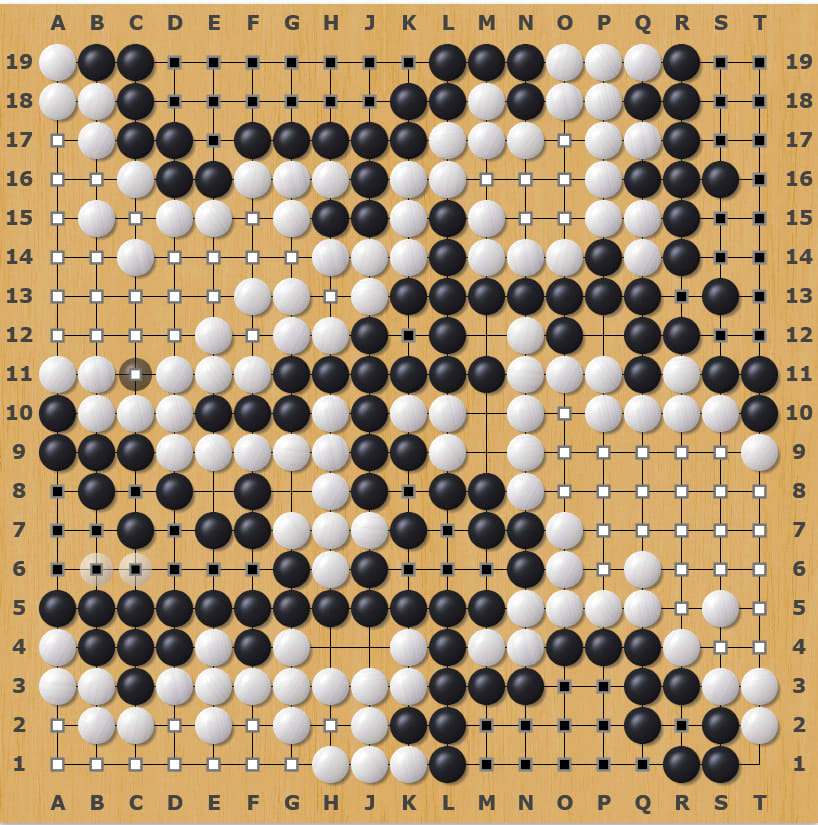

In Go you try to encircle areas to make it your territory. Additionally you try to encircle the stones of your enemies with your own stones, while trying to not get encircled yourself. At the end the player who was more successful in encircling both the enemies stones and their own territory will win the game.

I am sure this explanation will leave the curious reader with many more questions. This is unfortunately not the place to answer these. However, your confusion is probably similar to the confusion of many beginners in this game. In fact, confusion is a very normal state of affairs here.

Unfortunately, I am also quite confused about Go. In fact, I am not a very good Go player at all even though I have played the game on and off for many years. Luckily, I have a friend who is! α is a European semi-professional Go player who has taught Go for many years. We have been talking about how the concepts of Manifold apply to Go. A frame I found most interesting. They have offered to give their insight on their process of teaching and learning in Go and how it connects to other games we play:

_

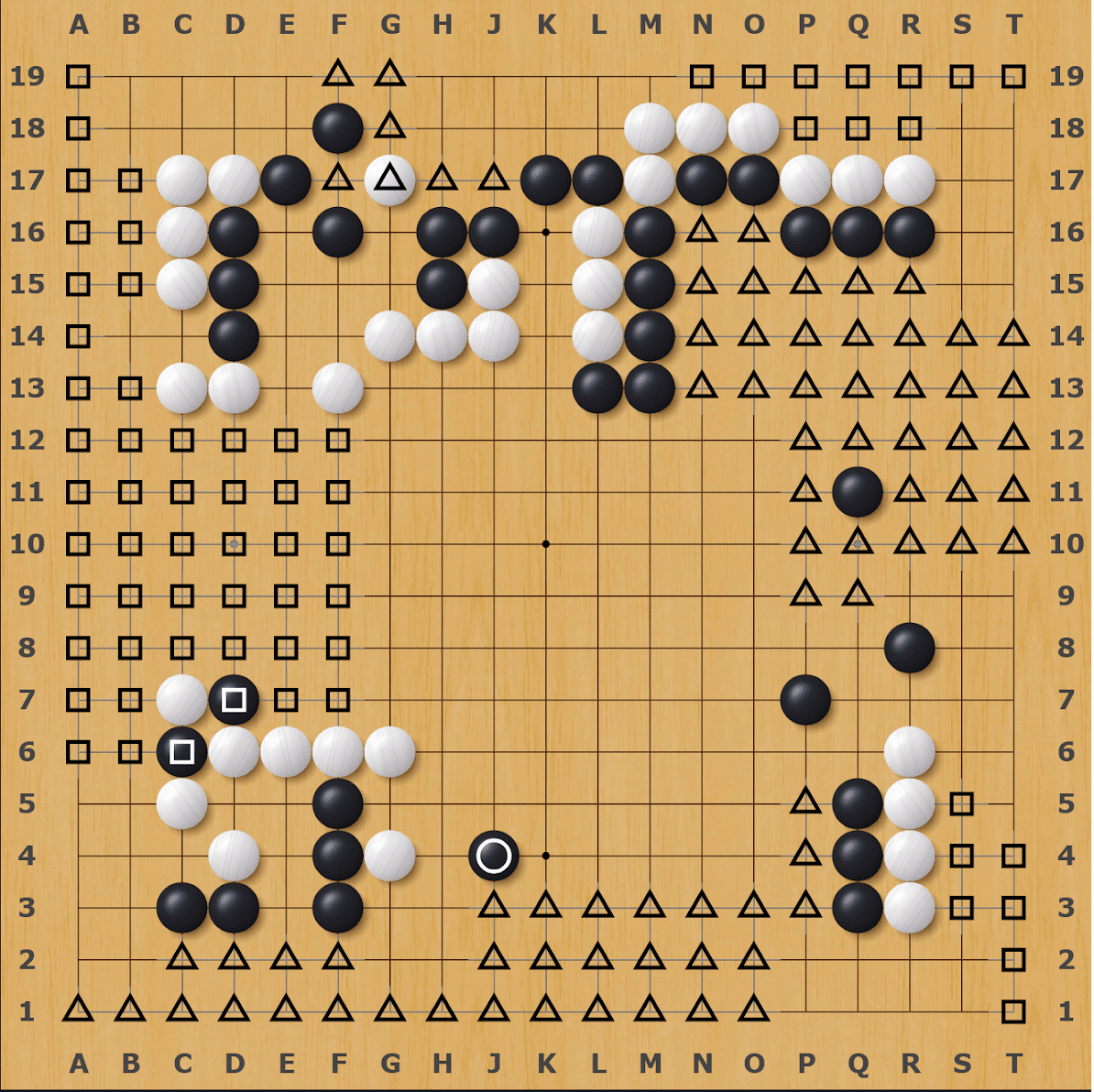

Years of teaching has taught me that it is an exercise in narrative analysis and deconstruction.

A player’s first Go memory may be the first narrative that they develop; it’s the first time you look at a position and it actually parses in your mind. It’s an oasis of refuge in the desert of manifold.

On the other hand, the young teacher’s perspective is that narratives are pesky things that hold back your students. An example of a ubiquitous narrative across amateur levels is that of ‘my territory’. Throughout a game, players identify parts of the board which are likely to belong to them or to their opponent. This allows them to effectively block out large sections of the board as already resolved and not worth thinking about. This proves to be maladaptive because it breeds status quo bias. A players’ map of ‘their’ territory becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, and they can refuse to give up ‘their territory’ even when other options become available.

I cannot count how many times I was scratching my head over a student’s decision before they explained to me that they were ‘keeping their territory’. To stronger players, such oases of meaning weaker players cling to seem arbitrary and limited - prisons of the mind.

The uncomfortable truth, however, is that stronger players live in a tense symbiosis with their own imperfect narratives. Human words like ‘attack’, ‘defense’, ‘influence’, and even ‘taste’ among many others are projected by even the strongest go players onto a fundamentally inhuman board. This is unavoidable. The experienced teacher recognises that narratives are as much oases of sanity as they are prisons of the mind. Every narrative is a way of making sense of the world, as it stops you from understanding it better. A formative experience I’ve had in my teaching is finding a defective narrative in a student, and realising that I had (correctly) given it to them years ago in a previous stage of their development. My job isn’t to frown on my students’ ‘primitive’ narratives, it’s to understand the role they serve and how they should be refined, maintained, or replaced. Learning is a fundamentally cyclical process of finding an oasis of meaning which makes your model of the world clearer, then becoming dissatisfied with its insufficiencies and leaving in search of something more.

After years of teaching, I have grown familiar with the lands of manifolds walked by my students. Experience as a player and a teacher gives me a bird’s eye view of their history, their current state and their proximate environment. Students’ stories blend into each other and all the narratives I’ve seen before help me write the next one.

Nowhere is the advantage of (relative) omniscience with respect to a weaker student so obvious as when it is absent; teaching oneself is the hardest thing of all. You’re already at the edge of your known world, and leaving an oasis of sanity to an unknown part of the world - intentionally assuming the role of those who know nothing, and doubt everything - is a profoundly hard thing to do.

The reluctance to question a familiar narrative is considered characteristic of people who are close-minded or uncritical, but it is ubiquitous and is telling you something important. Not having anything you actually believe in is disorienting and borderline paralysing. The moment you choose to distrust a narrative and subject it to scrutiny, it ceases to be something you can trust in. In the limit, the naïve deconstructivist forgets everything they ever learned, and feels like they are again a beginner. (א: Isn’t that supposed to be a good thing?) I’m generally quite a zealous and ambitious deconstructivist in Go, and I have gone wrong before by completely shooting my or a student’s confidence in their ability and understanding.

On the other hand, I hope I have made clear that some narrative deconstruction is an indispensable stage of the cyclical process of learning. It is hard and it is hard for good reasons, but it is the fundamental process through which you progress. Meaningfully changing involves being willing to question your narratives, but also to recognize the costs

that comes with that scepticism, and to understand your tolerance to being confused.

So, narratives are computationally efficient, but fundamentally misleading. Narratives keep you from being hopelessly confused and paranoid about your world model, but questioning them is a necessary condition for learning. The question then becomes, when do you question your beliefs, and when do you choose to trust them? One observation I found useful in answering this question is that problematic narratives are often the ones I’m not actively thinking about. If I’m already familiar with a problem, there’s a good chance I’m looking for and will find a fix. Conversely, many of my biggest regrets from competitive Go are associated with catastrophic decisions I made routinely and thoughtlessly– decisions where I didn’t even realise I was making one. This motivates a meta-strategy which is simply awareness. Narratives have a crucial function in saving computation, and this means that many (dys)functional narratives will be invisible to you unless you make yourself look. The way I have most often brought invisible narratives into my view involves noticing the things I want to avoid. For instance, if I notice during a game that I’m averse to a particular board position, but I can’t quite explain why, this is a sign that my background narrative system may be calling the shots. While I don’t always ignore or invalidate my qualitative feelings at that moment, simply recognising that I feel something without understanding why I feel it is already a step to interfacing with my narratives honestly.

_

Contains all games

Which mirror and sustain

The Maps of maps

Of how to win

And of how to play

The teachers teach

On what to learn

Where to go and where to turn

The leaders lead

From near to far

From here towards their Stars

To turn into the best at winning

Go where your teacher was

But to learn to go your own way

You must learn how to get lost

Learn to notice your own circles

So your paths and stars may cross

Today I have largely attempted to put you in the kind of frameworks I have been moving in for the last few years. In this my friends have helped me enormously. There are many other frames in which this topic could be seen in. Some of those I could discover in conversation and reading in recent years. Through the frames of others I could build and rebuild my maps (and metamaps) of the world again and again. By recapitulating some of the narratives and the narrators that surrounded me I hope I could impress some of my paths through manifold unto you. While I tried to share some paths of others that I have not walked myself, many paths were not taken today. For example there were several more potentially good ideas on how to create models and meaning that were recommended to me while I was thinking about Manifold. I found them interesting and indeed related to what I had to say here. I have not walked these paths sufficiently so far however, to comment on them.

I have many half formed intuitions on all the implications these frames have on different aspects of life. I will refrain from further expanding on that for today. It seems futile to try to put into words what is as of yet unformed in me. The possible paths that fork from this way through Manifold are too many to cross for now. Instead I invite you to reflect on what we tried to talk about here. What associations did it create in you? What frames of yours did it move into your awareness? I invite you to try synthesizing the frames that were new to you with all the previous narratives you have told yourself about whatever Manifold means to you. I hope that whatever you come up with will prove useful to you on your own path towards your stars.

So go now all you wanderers

Upon all your multitudes of ways

I’m now on my way to א*

Where still Manifolds remain

Discuss