Published on September 29, 2025 7:27 PM GMT

I

The popular conception of Dunning-Kruger is something along the lines of “some people are too dumb to know they’re dumb, and end up thinking they’re smarter than smart people”. This version is popularized in endless articles and videos, as well as in graphs like the one below.

Except that’s wrong.

II

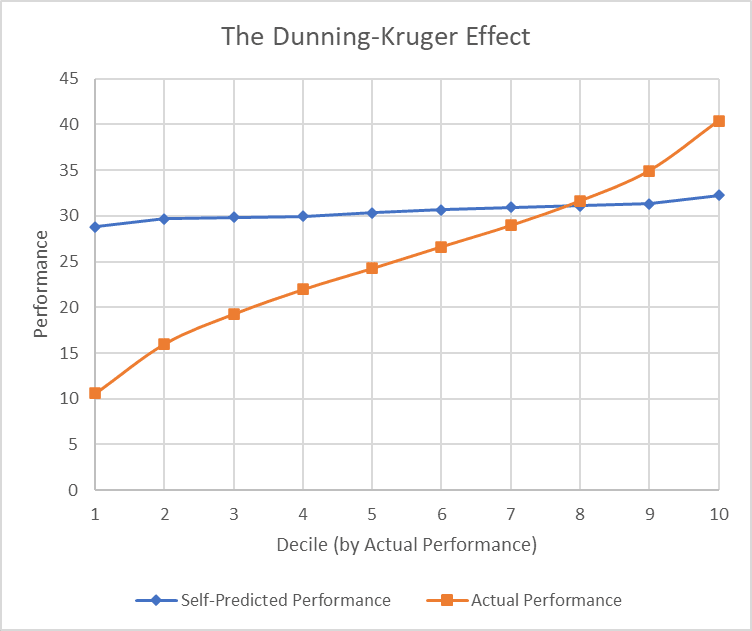

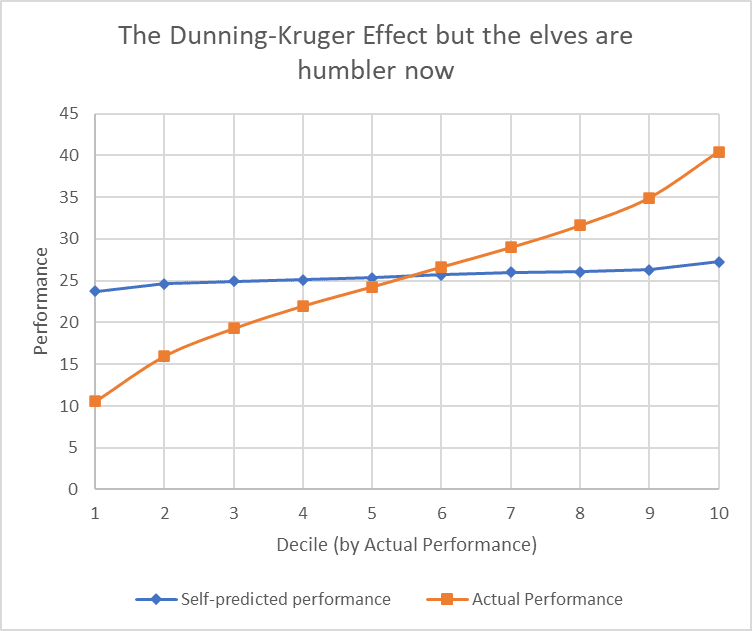

The canonical Dunning-Kruger graph looks like this:

Notice that all the dots are in the right order: being bad at something doesn’t make you think you’re good at it, and at worst damages your ability to notice exactly how incompetent you are. The actual findings of professors Dunning and Kruger are more consistent with “people are biased to think they’re moderately above-average, and update away from that bias based on their competence or lack thereof, but they don’t update hard enough”. This results in people in the bottom decile thinking ‘I might actually be slightly below-average’, and people in the top percentile thinking ‘I might actually be in the top 10%”, but there’s no point where the slope inverts.

Except that’s wrong.

III

I didn’t technically lie to you, for what it’s worth. I said it’s what the canonical Dunning-Kruger graph looks like, and it is.

However, the graph in the previous section was the result of a simulation I coded in a dozen lines of Python, using the following ruleset:

- Elves generate M + 1d20 - 1d20 units of mana in a day.M varies between elves.If you ask an elf how much mana they’ll generate, they’ll consistently say M+5; a slight overestimate, the size of which is consistent for values of M.

I asked my elves what they expect to output, grouped them by decile of actual output, and plotted their predictions vs their actual output: the result was a perfect D-K graph.

If you don’t already know how this happened, I invite you to pause and consider for five minutes before revealing the answer.

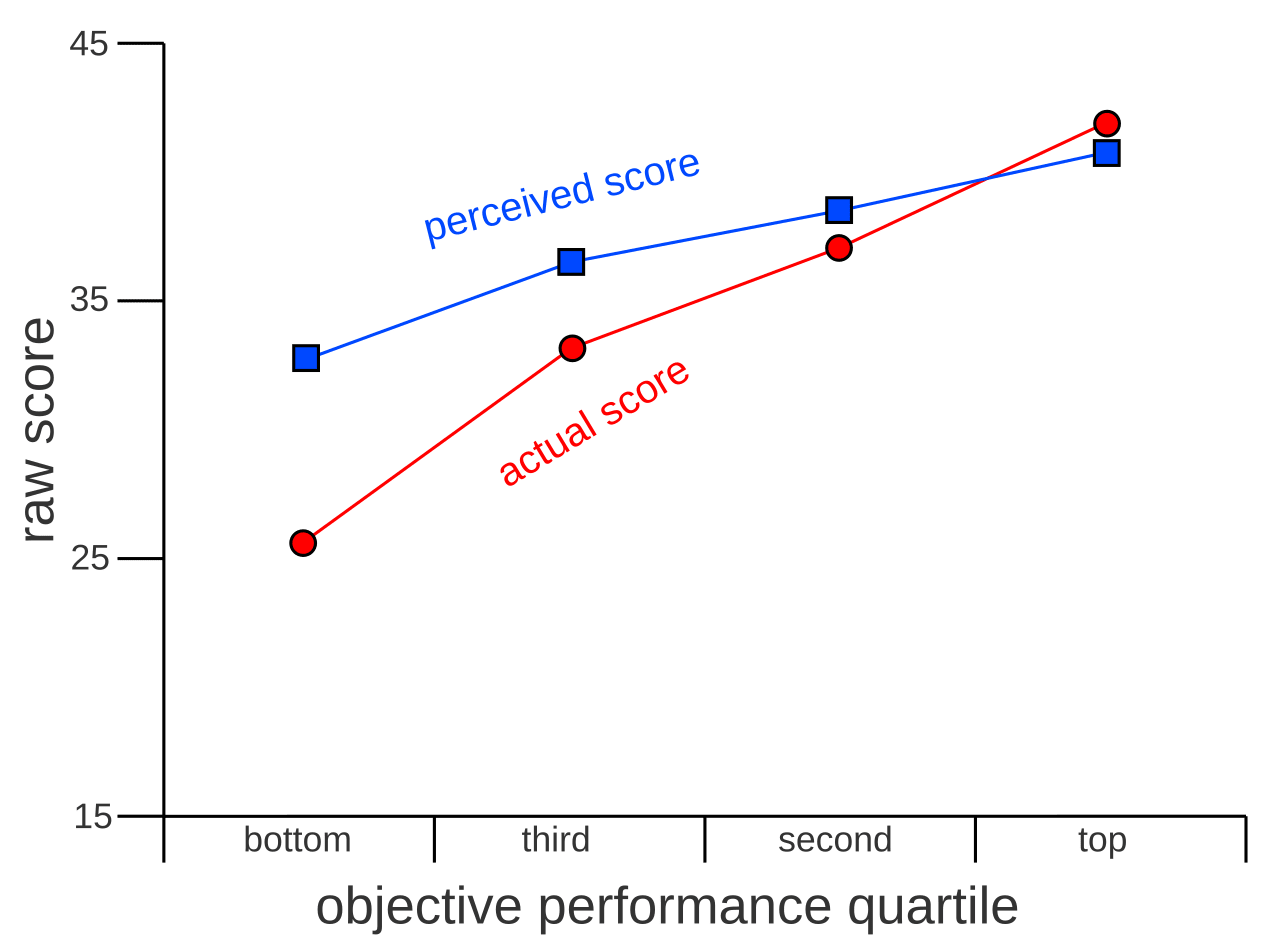

The quantiles are ranked by performance post-hoc, so elves who got lucky on this test will be overrepresented in the higher deciles, and elves who got unlucky will be overrepresented in the lower deciles. (Yes, this is another Leakage thing.)

You can see the same effect even more simply with Christmas Elves, who don’t systematically overestimate themselves: when collected in quantiles, it looks like the competent ones are underconfident and the incompetent ones are overconfident, even though we can see from the code that they all perfectly predict their own average performance.

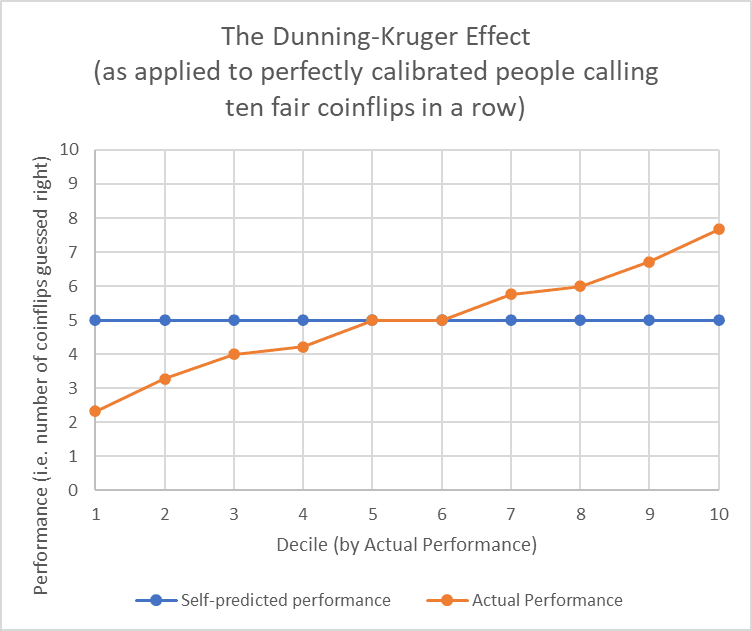

And, just to hammer the point home, you can also see it in a simulated study of some perfectly-calibrated people’s perceived vs actual guessing-whether-a-fair-coin-will-land-heads ability.

The original Dunning-Kruger paper doesn’t correct for this, and neither do most of its replications. Conversely, a recent and heavily-cited study which does correct for this finds no statistically significant residual Dunning-Kruger effects post-correction. So the thing that’s actually going on is “people are slightly overconfident; distinctly, there’s a statistical mirage that causes psychologists to incorrectly believe incompetence causes overconfidence; there’s no such thing as Dunning-Kruger”.

Except that’s wrong.

IV

. . . or, at least, incomplete. To start with, the specific study I linked you to has some pretty egregious errors, which are pulled apart here.

But even if it were planned and executed perfectly, “no statistically significant residual effects” is a fact about sample size, not reality: everything in a field as impure as Psychology correlates except for the things which anti-correlate, so you’ll eventually get p<0.05 (or p<0.0005, or whatever threshold you like) from any two variables you care to measure if you just study a large enough group of people.

But even if the study were a knockdown proof that D-K effects had a negligible or negative aggregate impact . . . “some people are too dumb to know they’re dumb, and end up thinking they’re smarter than smart people” is just obviously true. It’s obviously true because it’s an assertion which

A) begins with “some people”,

B) describes human minds, and

C) doesn’t break the laws of physics, biology, causality, or information theory.

(There are over eight billion of us now. It’s pretty hard to come up with possible things some people’s minds don’t do.)

The relevant question – especially for someone aiming to become more rational – isn’t “is this real?”, but “what’s the effect size?”, “how does it vary across populations?”, “how can I tell if it affects me?” and “is there another effect pushing in the opposite direction?”.

This all applies to the non-pop-sci version too. “I don’t know much about this, so I’ll falsely assume I understand a larger fraction of it than I do” is something you can probably recall having personal experience of, but so is “I don’t know much about this, so I’ll falsely assume the parts I don’t understand are incredibly impressive witchcraft to which it would be hubris for me to aspire”, and so is “I don’t know much about this, so I’ll falsely assume the parts I don’t understand are coherent and useful”; I can testify that I for one have been on both sides of all three of these at some point in my life.

Anyway, to sum up, my actual opinion: “there may or may not be a Dunning-Kruger effect in aggregate over any given group, but the original Dunning-Kruger paper and most of its replications make systematic statistical errors which render them useless; the original and pop-sci D-K effects are obviously true for some of the population some of the time but the same is true of any coherent psychology hypothesis including their exact opposites; miscalibration about competence still seems worth trying to fix but you’d need to check which mistake is being made.”

Except that’s wrong.

. . . probably, somehow. I don’t know what specific mistake(s) I made, and look forward to finding out in the comments. I’m very confident in my statistical and epistemic arguments, but I’m painfully aware the non-simulated object-level sources for this post were a handful of internet articles I read plus two papers I skimmed. Caveat lector.

. . . unless I’m wrong about being wrong?

Discuss