Published on September 8, 2025 5:20 AM GMT

The discourse on immigration to Europe is dominated by the migrants from Middle East and Africa in countries such as France, Britain or Germany.

At the same time, a very different dynamic exhibits in Poland, yet it is often implicitly waved away as just another case of the same thing. This lazy “think big and abstract, ignore the pesky on-the-ground details” attitude serves no one’s interests, least of all Europe’s.

In August of that year, Belarussian leader Aleksandr Lukashenko began offering “tourist” visas to huge numbers of African and Middle Eastern migrants, allowing them to enter Belarus, before forcing them to cross the Polish border. Lukashenko wanted to push “migrants and drugs” on EU member states that had opposed his domestic political crackdown. Suddenly, tens of thousands of migrants with no connection to Poland were pouring over the border, which at that time had no physical barrier and was lightly patrolled. Lukashenko hoped to exploit Poland’s need to comply with EU and international humanitarian law to destabilize the country’s politics.

In the initial wave of crossings, many vulnerable families crossed over from Belarus. But some of the migrants were single young men who were prone to fighting with border guards. Poland’s PiS government implemented a policy of automatically returning captured migrants to Belarus—a method of return known as “pushbacks.” Human rights advocates denounced the policy as a violation of the principle of non-refoulement, the international legal stipulation that refugees may not be returned to a country in which they are in serious danger. Initially, Poland’s liberals joined the condemnations.

But the government’s toughness proved popular: two-thirds of Poles feared the border situation would spiral into war and large majorities opposed accepting the crossers as refugees. Poland erected a border wall; Belarus provided migrants with ladders and wire cutters. The crossings continued. So did the pushbacks.

— Leo Greenberg: The Immigration Lesson Liberals Don't Want to Face

Emotionally, I lean very much toward the pro-immigration, pro-human-rights side of the debate, but setting emotions aside and looking at the issue from a pure game-theoretic perspective, it is not clear how is that going to solve the problem.

Lukashenko knows at a visceral level that an influx of migrants from foreign cultures tends to destabilize the political landscape of the receiving country. Here, a study by Laurenz Guenther provides numbers:

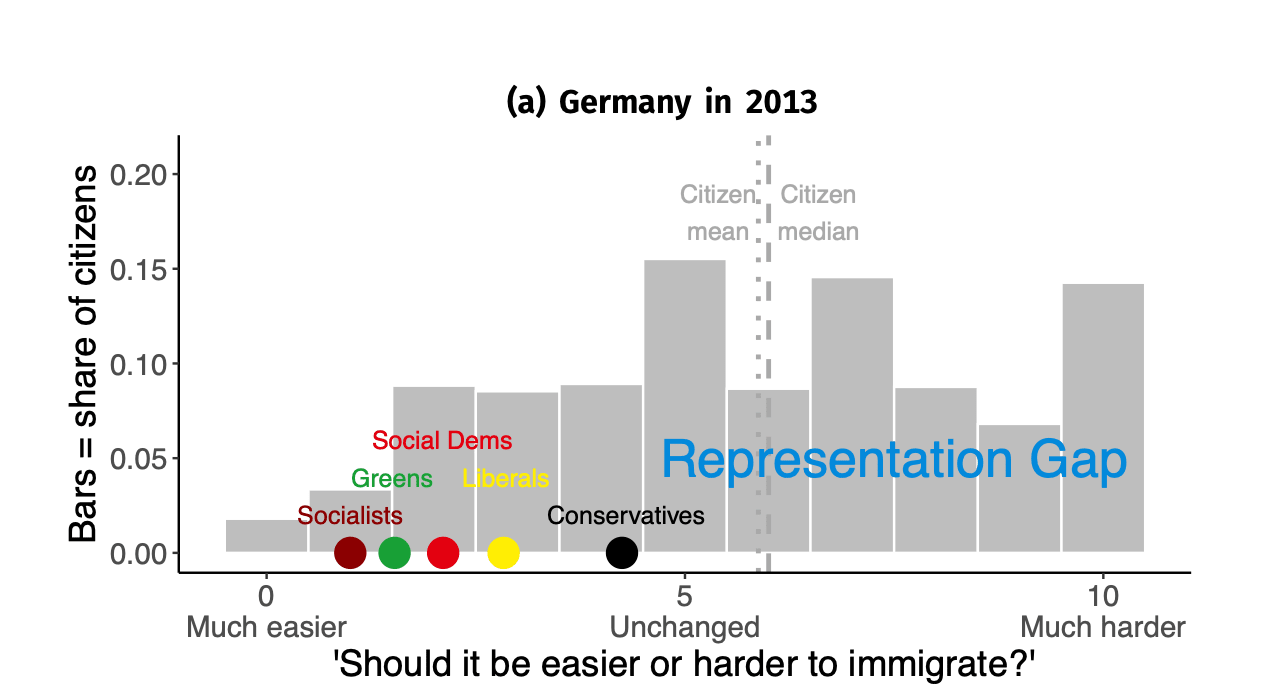

The grey bars represent voters’ attitude towards immigration. Vast majority of voters feel that immigration should be made harder. Yet, all political parties, including the conservative CDU, believe that immigration should be made easier.

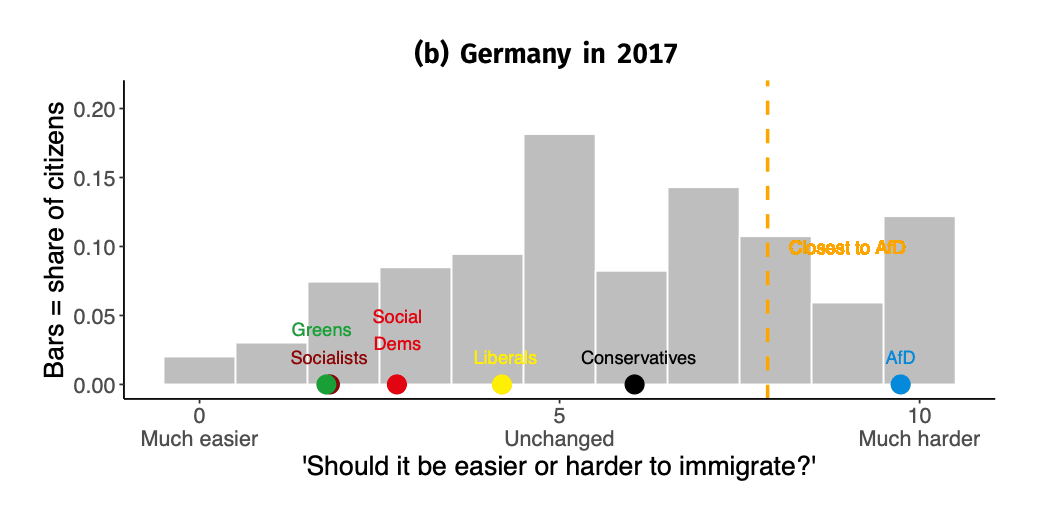

That was in 2013. And as you would expect in a functioning democracy, no policy preference, if it’s this salient, will remain unanswered for long. Just four years later, there’s AfD on the stage and it’s growing strong:

Here, Matt Yglesias provides an anecdote to show the above dynamic is perceived by the voters:

These charts resonate with what I heard from some older people at an AfD rally I attended in Munich during the 2017 federal election campaign. These people said they were longtime supporters of the Christian Social Union, [i.e. the conservatives in the chart above] […] They were annoyed that lots of foreign journalists were characterizing AfD voters as neo-Nazis or something, because in their view they were just voting to uphold the immigration policies of Helmut Kohl and many other mainstream German politicians of the past who nobody thought were Nazis. I raised the point that AfD really does have alarming neo-Nazi ties, and they kind of got annoyed and said their first choice would be for the Christian Democrats to be more restrictionist on immigration, but what are you going to do?

Lukashenko is taking advantage of this dynamic. He weaponizes immigrants to destabilize the political landscape in Poland. But how should Poland react?

Just sticking to the old, lose immigration policies is not going to work. Lukashenko can escalate and do so at a low cost. He can literally funnel half of Africa into Poland, which would in turn mean a full breakdown of the Polish political system.

To make things more complex, the legal framework governing refugees is based on the Geneva Convention, which itself was shaped by the somber experiences of the Second World War. At the time of its adoption, however, nobody imagined that the right to asylum might one day be deliberately exploited by a hostile state.

Fighting back against Lukashenko thus means violating Geneva Convention, which, in turn, means that the whole thing poses a direct challenge to the credibility of the international legal order. (And yes, it’s not hard to guess what kind of leader would benefit from such a breakdown of trust.)

In theory, international law could be adjusted to address these new challenges. In practice, however, such changes are extremely difficult. The international legal system is designed, for reasons that there’s no need to explain, to last, not to be revised.

All that said, while Poland was agonizing over the arrival of thousands of migrants from Belarus, the war in Ukraine broke out, sending millions of Ukrainian refugees across the border and today, roughly 7% of Poland’s population is Ukrainian. Yet, despite there being some sour spots, this immigration wave has been absorbed surprisingly well and has enjoyed broad public support.

It is a hint that the policy of accepting refugees is not yet dead.

But how should a new policy, resistant to adversarial attacks, look like is far from clear. Immigration from South America to Spain is another example of a large immigration wave that works well, which makes one think of avoiding the political backlash by accepting predominantly refugees from culturally and linguistically similar countries. But try telling that to Jordan or Lebanon.

As for now, there is no clear answer and governments are drifting gradually toward more restrictive approaches, which isn’t great news for the migrants, nor for the affected countries themselves.

Discuss