Published on September 7, 2025 10:45 PM GMT

I don't think dehumanization is actually a thing.

More precisely, I think it's almost always better to think of “failures to humanize” rather than of “dehumanizing”.

Since the seventies, we've known that rational thinking mediates only a small proportion of our decisions. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman showed how people make decisions in two different ways:

- System 1: Intuitive, automatic, quick, implicit, and habitual. System 2: Rational, costly, slow, explicit, and infrequent.

Only a small minority of our decisions are rational. The rest of our decision-making automatically follows patterns that proved useful in our evolution. Some heuristics became problems when our environment changed and they were no longer adaptive.

When our brains evolved, our communities were small. There was no need to empathize with outsiders. With scarce resources, sharing with others could be harmful to one's own group.

Despite the world having changed, not treating the "out-group" as we treat our own remains wired in our brains. This easily allows us to enjoy cell phones without thinking about the brutal practices in mineral exploitation that help keep our phones cheap.

Not humanizing the "out-group" is actually the default and requires no active effort. Despite this, we speak of "dehumanizing" as an action, when it's usually better to look at the problem the other way around.

The rational consensus of treating humans well

Throughout history, human rationality has produced treaties on treating everyone equally, especially since modernity. In practice, these implicitly propose treating everyone as we would treat our "in-group."

When I hear people asking to treat others like human beings, what I interpret is: treat others how we would treat human beings if we met Enlightenment philosophers' moral standards. Otherwise, I find the phrase meaningless, because it's impossible not to treat a human like a human.

Enlightenment philosophers thought we were fundamentally rational, but we now know this to be false. Even so, modern states and human rights organizations are founded on Enlightenment intuitions.

It seems true that we treat people better when behaving "rationally." There's evidence that we empathize more with others when making the rational effort to imagine their emotions. Asking ourselves if what we're doing is right and then explicitly choosing what to do increases the probability of treating people in the "out-group" as we would treat people in the "in-group." Unfortunately, for most people, reason almost never makes the choices.

Most arguments are rationalizations

On top of that, when we make a heuristic decision and are asked why we made it, we tend to respond with a rationalizing argument.

Suppose someone asks us what we think about a public policy defended by our political party. Most people would say they agree. Most people would also disagree with the same policy when told it's defended by the opposing party. This reveals that a key factor in making that decision is the bandwagon effect among the in-group.

However, when asked why they agree or disagree with the policy, most people give explanations about why they think it's good or bad, while grossly underestimating the importance of the bandwagon effect.

This effect generalizes. Even though most decisions depend on heuristics, people tend to give explanations as if decisions had been rational. In fact, they usually end up convinced that the decisions were actually founded on rational thought in the first place.

Moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt hypothesizes that most of our rational thinking serves to invent explanations, not to actually make decisions. From his perspective, rationalizations help us justify our actions to others.

Taking this into account, when focusing on "dehumanizing discourse," we might actually be focusing on rationalizations of previous heuristics. If so, we would be looking at effects, not drivers, of social violence—in other words, addressing symptoms instead of actual causes of the problems.

I think that most dehumanizing discourse actually stems from situations in which:

- We have the usual reaction of being insensitive to others' troubles.It's hard to find rationalizations other than dehumanizing discourse.

For example, tragedies always happen. I could donate much more than I actually do. No one asks for explanations, but if they did, I could argue that it's impossible to help everyone, or that some problems are systemic and require systemic solutions. I don't need to compare anyone to an animal to give explanations.

Some businesses rely on third-world semi-slave labor. There are open-pit mines that corrode human lungs and sweatshops that steal the childhood of kids. When held accountable, businessmen can give economic arguments to show that someone else would do the same if it weren't them. Again, no need for animal comparisons.

However, when a journalist asks a minister about bombing innocent children, it's hard to give an explanation that sounds nice. Suddenly, the only reasonable explanation the minister finds is to compare the victims to savage dogs.

At the psychological level, the three cases are similar. The minor inconvenience of losing money, making less money, or worrying about a conflict feels more important than the huge impact these decisions have on distant people. They look different when giving explanations, but that isn't what really mattered when making the decision. The default is not to worry about others' tragedies, and this is only sometimes rationalized through "dehumanization."

When the minister claims that children are dogs, the damage was already done.

Humanizing is hard

Well-meaning efforts to fight "dehumanization" on the rational level have not scaled. They tried and failed to stop the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, the Cambodian genocide, the Holodomor, the Bengal famine, etc. Frequently, large-scale phenomena that require generalized attention and rational thought do not happen, because rational thought is costly and infrequent.

I think that the cases in which we empathize with people in the out-group are mostly explained by causes that our in-group cares about.

In his book Behave, Robert Sapolsky cites an observation about implicit racism. When seeing people from an out-group, most humans' amygdala activates, which is a part of the brain usually related to stress responses. However, in people who identify as progressive, the prefrontal cortex sends a signal to the amygdala that stops the stress reaction. This doesn't happen as much in people whose in-group doesn't value tolerance.

The prefrontal cortex is related to rational thought and tends to deactivate when we're tired or hungry.

From an evolutionary perspective, and building on Jonathan Haidt's observation, it seems that even the rational overriding of our in-group bias depends on our in-group preferences. I find it curious that most of my friends empathize with either Israelis or Palestinians, while none of them have strong feelings about ethnic conflicts in Myanmar.

I suspect that making the rational effort to empathize with others when this doesn't follow our in-group's values is extremely costly. Even though we can push ourselves and our friends to do it, we can't expect it to scale. It goes against our heuristics and incentives, and we can't expect everyone to just do it.

So if dehumanization is not a thing, and making an effort to humanize doesn't scale, can we do something?

Network-level interventions

Many of our heuristics react predictably to our social network. Maybe it's easier to change the social network in a way that reduces violent or harmful heuristics than to change hard-wired patterns in our brains.

For example, Robert Sapolsky mentioned three mechanisms that proved successful in mitigating violence between groups. The first two are morally problematic.

The first solution is simple: If groups don't meet, friction doesn't arise. This is the preferred option for racists and xenophobes. Even though it can mitigate explicit violence, it doesn't necessarily stop implicit forms of violence like ghettos or segregation.

The second solution is assimilation. When populations of different groups are mixed so that most of everyone's neighbors are from other groups, violence levels drop as well. It's as if virtual frontiers between groups are dissolved. For example, violence at soccer matches is more common when fans are separated than when there are mixed stands.

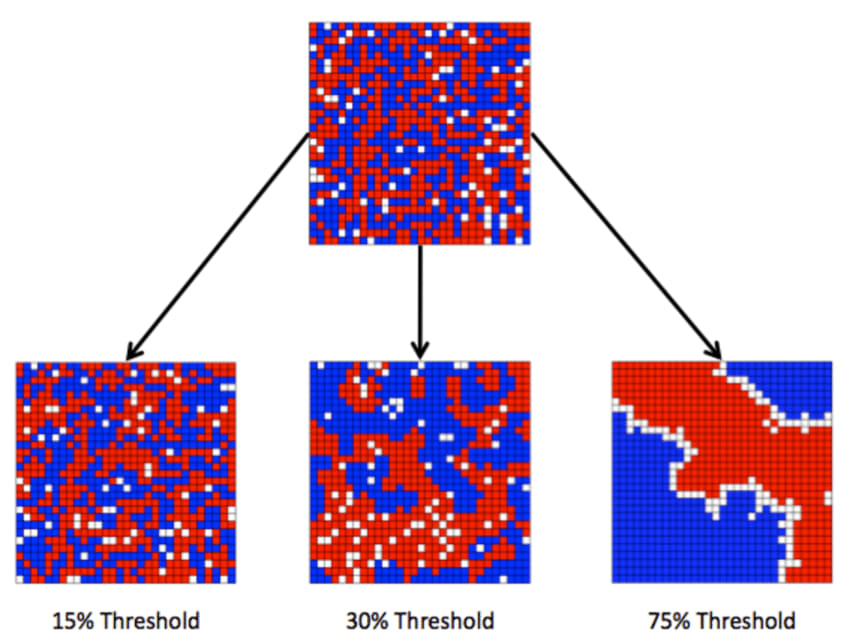

Unfortunately, Thomas Schelling's work shows that it's hard for full assimilation to emerge naturally. The preference of not being a small minority among our own neighbors is enough for partial segregation to emerge (with "patches" full of people of the same group).

The third mechanism Sapolsky suggests is economic equity. When inequality and/or poverty decrease, it's less likely that brutality between groups will emerge.

Human violence is usually associated with the perception of hierarchies. We share the heuristic of being violent to guard our rank with orangutans and chimpanzees. But human hierarchies are the largest in the animal kingdom, and extreme inequality drives violence levels to rise.

I wrote this because I suspect that fixing our attention on "dehumanizing" discourse may be futile. If it emerges from upstream causes, we shouldn't try to dissipate the smoke to stop a fire.

When trying to address social-level biases, it may be easier to address the root influences in the social network than to expect everyone to behave rationally.

Discuss